Sámegillii

Sámegillii  På norsk

På norsk

Po polsku

Po polsku

Do you know Sami school history?      Sámi skuvlahistorjá / Samisk skolehistorie (Sami School History) is a series of books published by the publishing house Davvi Girji. In about 200 articles in 5 volumes there is told about the experiences of Sami children in Norwegian schools, and about the changes in the educational politics of the Norwegian authorities towards the Sami population. The books are published with parallell text in Sami and Norwegian language. In this web site some of the articles of the first book are also published in English. It would be too much to translate it all, so to make this history available to a greater public, we are translating a series of newspaper articles, which sorted by topics make a summary of stories in the books. So far there are 28 articles published in Sami language by the Sami newspapers Min Áigi and Ávvir. They are also published here in Norwegian and the English version will be published gradually as they are translated. These articles are edited by the main editor, Svein Lund. Besides him the editing board of the book series consist of Elfrid Boine, Siri Broch Johansen and Siv Rasmussen. |

As Jon Ole recounts, most of them soon returned south. But others stayed, and some have now lived 40-50 years in Sapmi.

Most of them came straight from teacher-training college or they had only 6th form (2-3 years of further education), and many had never been up north before they started work as teachers. Everything was foreign to them; the environment, the culture, the language. Only the school-books and the syllabus were the same as in south Norway. They tried to do their job as well as they could.

Many of them saw that something was wrong and that they did not have capacity to give the pupils a suitable education. But they were not prepared to admit it, either to the pupils or to the parents. To the pupils, the teachers represented the state and power. While collecting articles for a Sami school-history, we received an account of a couple of teachers, a man and wife who were, on the basis of the article, clearly opposed to the policy of Norwegianization of the time. I showed this to a man who had been their pupil nearly 50 years earlier, and he said:

“It’s only this year that I have been able to read the pamphlets that these teachers have made of their memories from Sirma. There was something that really surprised me when I read it. It was that they thought the lessons ought to have been in Sami. That they were, in fact, opponents of the policy of Norwegianization that they were forced to practice. We pupils didn’t understand that at the time. For us, it was the teachers who represented the supreme authority. We didn’t, of course, see the people the teachers had above them and the laws and rules that governed them. We thought it was the teachers’ fault. Were they really people who cared about the Sami’s situation? I must say that we, the pupils, didn’t have that impression.”

(Per Edvind Varsi's story, SSH-1)

|  |

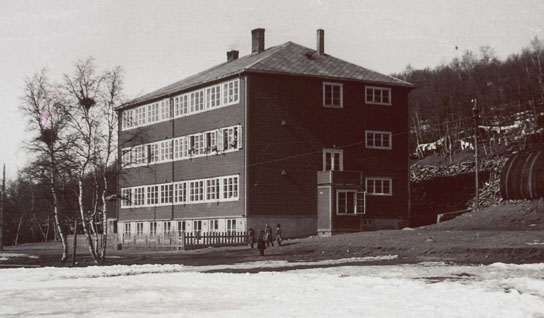

| Polmak old boarding school (Photo: Ivar Skotte) | Per Edvin Varsi (to the right) tells: "In summer I went fishing together with Einar Gullichsen. Then we were the best friends. But in winter at school the relation was not same good.." (Photo: Sissel Gullichsen) |

I was full of a will to fill the empty space left by the absent parents, but the qualifications were lacking. For that, my knowledge of the language was all too poor. It was no use waving my university exam for, in practical terms, I was completely helpless. ...

I attempted, with my bad Sami pronunciation, to say some friendly words to the little ones, but there was no reaction, either to my vocabulary or to my smile. I was only met by fifteen pairs of eyes that constantly followed me and my every move with a curious wonder. What thoughts lay behind that staring glance? The big boy on the back row looked as if he wanted to say: “Why do we have to sit still for so long? That isn’t for us children of reindeer-herders. Besides, father and mother said expressly that we were to go to school.”

(Ottar Bondevik's story, additional material to SSH-5)

"There was a shortage of teachers all over the country, and through the radio and newspapers they encouraged also people who had done upper or lower secondary school exam or equivalent education to sign up to rebuild the school in the north.

I was one of those who followed this encouragement, and a day in the end of September 1946 I boarded the old "Midnattsol" in Ålesund with the suitcase in my hand and a telegram from the superintendent of schools in Finnmark in my pocket. . ...

The barrack city which was there so silent and grey in the twilight, and the unknown language which sounded so unfamiliar in my ears gave me a sensation of being far away from home, I was in Norwegian borderland. My body was tingeling with excitement. As the clock drew close to nine I called the office of the superintendent of schools – where I talked to the superintendent himself who wished me welcome in the dialect of Sunnfjord (again an unexpected contrast). ... Aarseth told me that I should teach at Meskelv school in Nesseby commune, which was a community school divided in two, that the school building was a barrack with one classroom and a bedroom and a kitchen for the teacher. Most of the pupils were bilingual Sami/Norwegian, but "not all of them are fluent in Norwegian", he added. Otherwise there were no instructions for the greenhorn, except that I was starting an important work and had to do my best.

...

I sensed that I had entered a way of socializing which was completely unknown to me and my tools for thinking weren't sufficient to systemize and understand it. As many others I arrived more or less straight from the gymnasium and had barely seen anything but the life in the countryside in Sunnmøre. I was more or less blank when it came to knowledge about Sápmi. I had probably read Friis' novel – a book by Fønhus and other travel literature – and I had listened to Sami-mission travelling lay preachers, but I soon realized that this weren't applicable in my situation. And I wasn't a pedagogue either. My own curiosity and my moral compass I had from home became my tools for navigation. "

(Harald Eidheim's story, SSH-1)

| Harald Eidheim with pupils in Polmak. The pupils are: Nils Johannes Porsanger, Frøydis Aslaksen, Ingrid Dolonen, Elna Holmgren, Marit Tapio, Edvin Johnsen. (Photo lent by Harald Eidheim) |

My experience is that of the southerner, since it was as a teacher that I came from the outside to start my first job in the classroom 20 years ago. The place was Lakselv and the class 8 B; 32 pupils who were now starting on their final two years of the recently introduced 9-year school. Strangely exotic Finnmark -, it was like arriving in a foreign country: “Everybody speaks Norwegian. Nobody needs to speak Finnish or Sami”, was the message we were given.

I at once became an obedient sergeant, who took his Norwegian duty seriously. There was no need for either Sami or Finnish here! – Until the director of the boarding-school made me aware of the fact that Sami and Finnish were their mother-tongue and that the boarding-school was their second home. Today, 20 years later, it’s easy to get annoyed. At the time though, the Norwegian school had little or no room for local knowledge or other cultural perspective than what the text-books said was the correct teaching. Besides – what did a recently trained teacher from the south know about Porsanger and Finnmark?!

For me, this encounter with Finnmark was an encounter with the unknown Norway! “Yes, today it’s 20 years since the Germans scorched this place”, said the shop-owner and host as he poured us gaping southerners a cup of coffee. As newly graduated teachers, we were qualified to teach at a Norwegian school, but totally lacking any form of local knowledge, let alone any cultural understanding of the environment or area from which our pupils came.

This gradually became a concern -, but also an inspiration to find out more about Porsanger, Finnmark and northern Norway. It became a search for knowledge and understanding of what had happened through the ages.

It was here that the historian in me was born.

(Anders Ole Hauglid's story, SSH-5)

“It wasn’t always easy to get teachers to come to an out-of-the-way place. Those who came were seldom from Finnmark, but were more often than not people from the south, with tuneful dialects and loosely hanging clothes. Some ate seaweed for dinner, while others liked to go around barefoot, all the year round. We pupils got new ideas and something to giggle at during the breaks. These teachers were probably just as ignorant as us of the fact that the census in Loppa from 1845 shows that 60,6% of the population were Sami.”

(Lone Hegg's story, SSH-2)

Here you find all the articles in the series:

28.09.2007 Why Sami school history?

05.10.2007 Boundless ignorance

12.10.2007 Southerner-teachers encounter the Sami language

19.10.2007 The start of Sami beginner instruction

26.10.2007 The start of education in reindeer-herding

02.11.2007 From Sami to Norwegian vocational training

16.11.2007 Struggle for Sami gymnasium

28.11.2007 School experiences of Norwegian speaking Samis

14.12.2007 Resistence against Sami language and culture

25.01.2008 A strange world

23.05.2009 On Sami teachers

30.05.2009 Life in boarding school

06.06.2009 Sami pupils were bullied

13.06.2009 Sami content in the teaching

20.06.2009 Pupil as interpreter

04.07.2009 How the children quit speaking Sami

10.09.2010 God does not understand Sami

08.10.2010 The point of view of the Norwegianizers

13.10.2010 Men of the church defending the Sami language

02.12.2010 Sami teachers in old times

09.12.2010 Boarding school life in old times

18.12.2010 Sami pupils in special schools

14.01.2012 The parents' struggle for Sami education

21.01.2012 Reluctance and absence

28.01.2012 The school during the war

04.02.2012 Reconstruction and barrack schools

11.02.2012 Curriculums - for Norwegianization and for Sami school

18.02.2012 The great struggle of the curriculum

11.05.2013 Sami language forbidden? – 1

xx.05.2013 Sami language forbidden? – 2

xx.05.2013 Folk high school for norwegianization

xx.06.2013 Folk high school against norwegianization?

xx.06.2013 Skolt Sami school history – does it exist?

xx.06.2013 Duodji education – in and outside of school

xx.06.2013 Sami in the cities

xx.07.2013 Sami language in teacher education

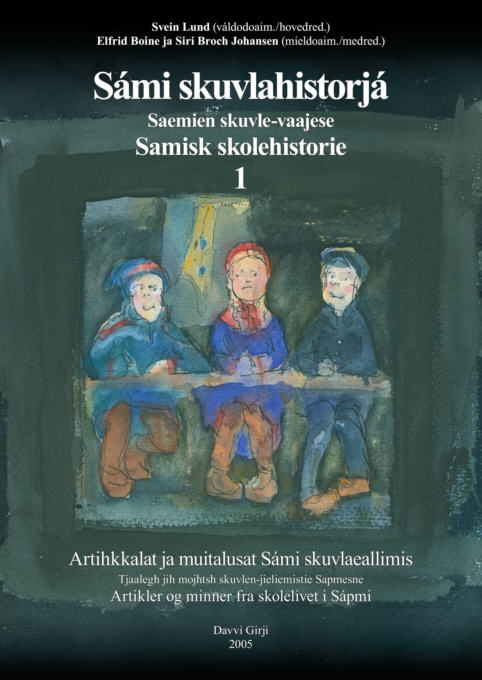

Sami school history 1

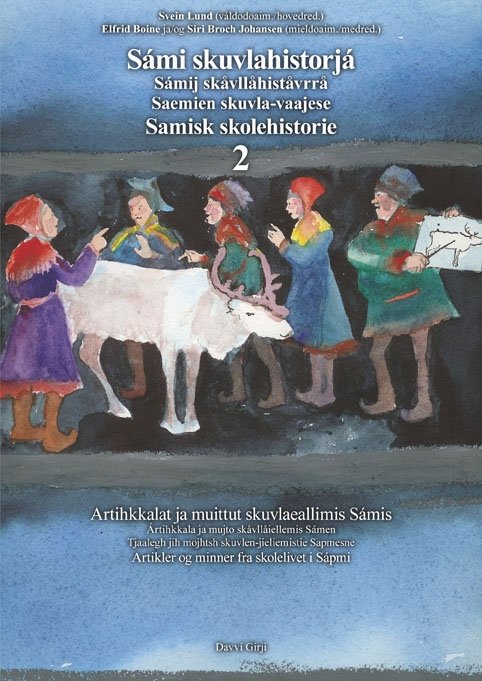

Sami school history 2

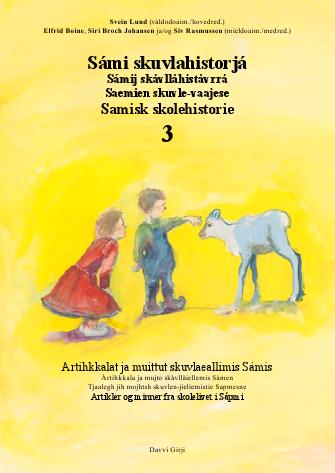

Sami school history 3

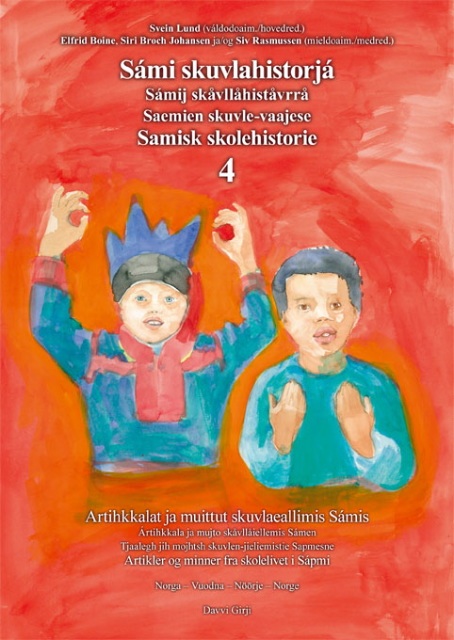

Sami school history 4

Sami school history 5

Sami school history 6

Sami school history - main page