Sámegillii

Sámegillii  På norsk

På norsk

New articles for Ávvir 2013

33.article – 21.09.2013

Do you know Sami school history?Here we present a series of articles printed in Sami language in the newspapers Min Áigi and Ávvir from 2007 to 2013. The basis of the articles are stories which have been collected through the project “Sami school history”. There are edited 6 books with stories and articles from school life in the Norwegian part of Sápmi. In these articles there are many quotes from the books, and we refer to the articles the quotes are taken from, to make it possible to read the entire stories there.The chief editor of Sami school history, Svein Lund, is editing this series of articles. In addition Elfrid Boine, Siri Broch Johansen and Siv Rasmussen are part of the editorial staff.

|

In this article we look at the background for the situation of the Skolt Sami today, and at the school experience of the Skolt Sami in Norway. This is a very shortened version of a longer article in Sami School History 6.

In the 1500’s the Skolt Sami were christened by Russian Orthodox missionaries, who erected a monastery in Petsjenga as well as several churches, among these those in Boris Gleb and in Neiden. The Skolt Sami were therefore counted as Russian citizens, but for a long time Russian, Norwegian (Danish) authorities demanded taxes from them.

The Skolt Sami had of old six siidas. Before the border was drawn between Russia and Norway in 1826 three of these made out a common district of Neiden, Pasvik and Petsjenga, which both of the countries made claims to.

In 1826 the border was drawn straight through the areas of the Pasvik siida and the Neiden siida. This resulted in most of the Pasvik-Skolt Sami being located on the Russian side, and through subsequent political changes their decendants ended up in Finland. Most of the Skolt Sami from Neiden chose to remain on the Norwegian side, and from 1842 they were Norwegian citizens.

After the First World War the Russian part of the old Pasvik siida and Petsamo siida areas, as well as parts of the Suenjel siida, became Finnish, but with the Second World War, Russia (The Soviet Union) reclaimed this. The inhabitants of this area were to a large extent evacuated downward in Finland, and most of them never returned to their old dwellings. A few years after the war the Finnish government made sure that the evacuated Skolt Sami were given new homes in Finnish territory, but still within old Skolt Sami land. The biggest of these were Čeʹvetjäuʹrr / Sevettijärvi, and this village has later been the most important centre for Skolt Sami language and culture.

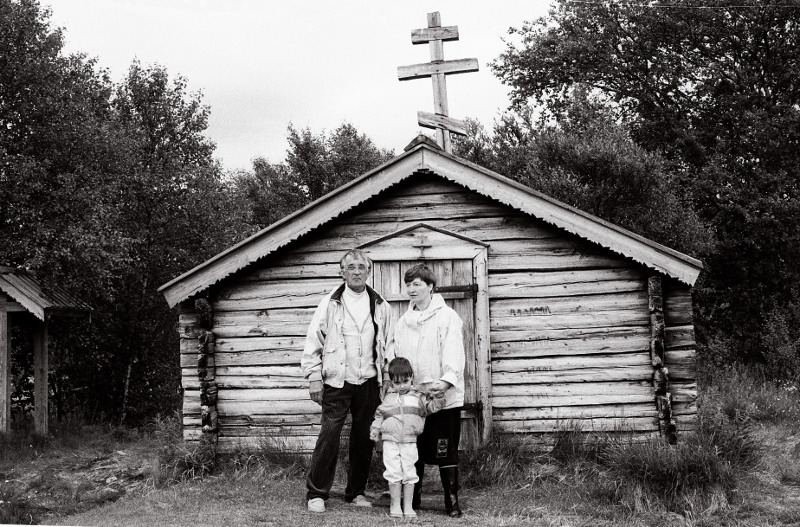

| St. George's chapel was built in 1565:s, but the building which is today is probably built in the beginning of the 19th century. This is the smallest church in Norway and the only ortodox church in Northern Norway. The picture is made in 1990. In front of the chapel is the at that time leader of organisation "Skoltene i Norge", Frans Halonen, totether with his wife, and his son, who was the first to be baptized in the ortodox chapel in 60 years. (Photo: Svein Lund) |

Up until the First World War the Russian priest in Boris Gleb visited the parish of Neiden, and held service there. Konstantin Shchekoldin, priest in Boris Gleb, published in 1895 the first Sami textbook on the Russian side. But there was little he could do to affect the conditions of the Skolt Sami in Norway.

In 1891 Johannes Haaheim from Western Norway came to Neiden as a teacher. When Fossheim boarding school in Neiden was built in 1905 as one of the two first state boarding schools in Norway, he became the headmaster. He was a firm supporter of the norwegianization policy. Because of large immigration from Finland, Finnish was now the dominant language in Neiden. The Skolt Sami learnt both North Sami and Finnish, and there were ever fewer who spoke Skolt Sami.

Amund Helland wrote in Norges land og folk – Finnmarkens Amt[1], published in 1906: «The Skolt Lapps in Neiden are Greek Catholic, and the priest in Boris Gleb visits them… The Skolts don’t send their children to Norwegian schools, and no one has thus far attempted to impose the judgements of the law upon them.»

When the book was published this was already outdated. After threats and fines the Skolt Sami agreed to send their children to school from 1905.

| In the cemetary of Neiden lies the last one who spoke Skolt Sami language in Norway, Jogar Ivanowitz. The two crosses on the stone shows that Jogar belonged to the ortodox church, while his wife was a Lutheran. (Photo: Svein Lund) |

By law the Skolt Sami as «dissenters» were exempted from Christian teachings in school, but it didn’t take long before they also accepted being taught this. They also went through confirmation, becoming members of the State Church. The adults were also affected by the Laestadianism, which was the dominant religious direction in the district, and after a while there were only a few older Skolt Sami who clung to the Orthodox Church.

As other small rural schools Fossheim is always under the threat of being closed down in the next municipality budget. This makes both teachers, parents and pupils unsafe, and young families are uncertain whether they dare gamble on a future in the village. For the school this means that it is hard to get money for necessary equipment and maintenance.

| Headmaster Elin Steigberg shows a poster with Skolt Sami numbers, which is made in the project «Skolt Sami culture across borders». (Photo: Svein Lund) |

Otto is one of the last to have grown up in Neiden who can speak Skolt Sami, at least partially. Today there are several speakers of Skolt Sami who live in Neiden, but they have grown up on the Finnish side.

In the spring 2012 there was for the first time organised a course in Skolt Sami language in Neiden. There has also been made teaching material for the teaching of Skolt Sami language in Norway.

In Sør-Varanger today you do not see much to indicate that Skolt Sami possibly is the oldest language used in the area. While they on the Finnish side have used Skolt Sami together with Finnish on road signs in Skolt Sami inhabited areas, there are mostly just Norwegian names on the Norwegian side in Sør-Varanger. The few Sami names that are visible are North Sami.

In addition to the aforementioned language course in Neiden there have also been language courses in Russia and Finland. The project has organised several courses in Skolt Sami arts and crafts. Knitting courses with Skolt Sami patterns have been popular, and they have also had courses in fish skin work and pearl embroidery. There has also been made and printed simpler information material about the Skolt Sami. In the spring 2012 they had an information day for principals and a few teachers from district schools in Sør-Varanger, and in the autumn the same year these schools had a joint planning day in Neiden with emphasis on the Skolt Sami.