Sámegillii

Sámegillii  På norsk

På norsk

Articles about Sami school history

part 12 - printed in Ávvir 30.05.2009

Do you know Sami school history?Sámi skuvlahistorjá / Samisk skolehistorie (Sami School History) is a series of books published by the publishing house Davvi Girji. In about 200 articles in 5 volumes there is told about the experiences of Sami children in Norwegian schools, and about the changes in the educational politics of the Norwegian authorities towards the Sami population. The books are published with parallell text in Sami and Norwegian language.In this web site some of the articles of the first book are also published in English. It would be too much to translate it all, so to make this history available to a greater public, we are translating a series of newspaper articles, which sorted by topics make a summary of stories in the books. So far there are 28 articles published in Sami language by the Sami newspapers Min Áigi and Ávvir. They are also published here in Norwegian and the English version will be published gradually as they are translated. These articles are edited by the main editor, Svein Lund. Besides him the editing board of the book series consist of Elfrid Boine, Siri Broch Johansen and Siv Rasmussen. |

Here some pupils, teachers and employees tells how they experienced life in the boarding schools in the period 1947-70.

|

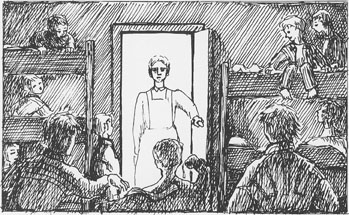

Room in the boarding-school barracks in Guovdageaidnu (Drawing Inger Seierstad) |

- We stayed at the boarding-school barracks. There the girls were on one side of the corridor while the boys were on the other. The beds were bunk-beds and there were two girls to a bed. The bursar and the maids (assistants) were all Norwegian speakers, nobody spoke proper Sami. The children had to do a

lot of work at the boarding-school. We had to wash the dishes, make sandwiches, and fetch firewood and milk. I remember that at the

boarding-school we got a lot of fish that had gone off. It was brought in from the coast in autumn so by spring it was rotten. It was

completely inedible and there was no way we were even going to try. Instead we went to relations of ours in the village and ate there.

(Elmine Valkeapää's story, SSH-1)

|

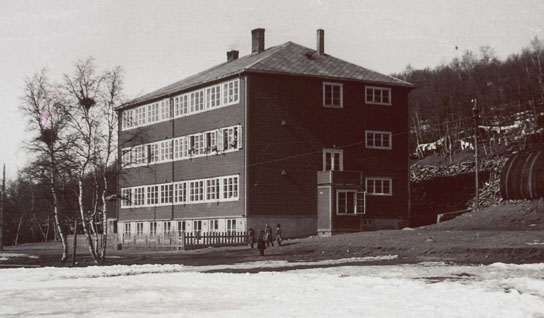

The old boarding school in Polmak (Photo: Ivar Skotte) |

The boarding school was an impressive building. With its three floors on a high foundation wall it really stood out in the landscape. The house was finished in 1938 and had survived both the war and the burning in 1944. There weren't any electricity in the village, but the boarding school had its own generator named Sakkeus. I don't know why. In the room next to the generator there was a room with accumulators. The system was made for the generator to charge the batteries. When they were fully charged we would have enough electricity for the classrooms, the dormitories and for the other rooms in the house, but not for cooking and heating. I soon realized that the maintenance of Sakkeus and the accumulators would be one of the main tasks in my position as manager of the boarding school.

The buildings were more than 15 years old, and quite run-down. There shouldn't be spent money on anything, because the village was waiting for electricity. Kraftlaget (an electricity company) had already started setting up poles both for high-voltage and energy distribution network. The boarding school had a system of central heating, which could be heated both with firewood and coke. When we heated with firewood I had to get up at a certain time during the night to fill the stove, otherwise there would be no hot water in the morning, and cold dormitories and classrooms. Coke was transported to the school when the ice on the river Tana was solid.

People from the neighborhood were hired to chop firewood and do other

kinds of work that could be dangerous. The pupils had the

responsibility to pile the firewood and make sure there were always

enough firewood in the kitchen and in the boiler room. I can't remember

whether there were problems linked to this job. As in any other home it

was natural that the children helped out with odd jobs. I was used to

this from back home in the farm where I grew up.

(Ivar Skotte's story, SSH-1)

– I started school in 1952. I attended the lower primary school in the boarding school in Breivik. At the time it was the only boarding school in the municipality that had been reconstructed after the war. The dormitory was in a very poor state, the roof was leaking and there was only an outside lavatory. I remember that the first time I saw a horse was when I came to Breivik. We had cows, sheep and goats in �yfjorden, but no one had horses.

The pupils in the boarding school came from different small villages in the municipality. Most of them had Sami background. I think many were in the same situation as I was; the parents spoke Sami among themselves and Norwegian with the children.

There were also pupils who came from Breivik in the school. They lived at home, and most of them were Norwegians. There was no division among the children based on their background, everybody played together and nobody stood out.

All of us had to do regular chores in the boarding school, saw wood, carry wood and coal and stoke the oven. We had to clean the dishes in the kitchen, all of the cooking pots had to be polished with steel wool. It was a terrible work with that steel wool. Since the roof of the school was in such a bad state we had to showel the snow off the roof to prevent it from falling down. That was our job too. And they sent us to the pier to get fish.

There was one matron or house keeper and a maid who cooked for us. We had to eat all the food whether we liked it or not. I can still recall the semolina porridge and the oatmeal porridge. It was not allowed to leave anything on the plate, and we could not leave the table before we had eaten everything. We had two different house keepers while I was there. One of them was very tough and strickt, so when the other one arrived it was as if reaching paradise.

At the time one was terribly afraid of lice. I do not think there were lice at Breivik school, but all of our bedlinen was treated with lice-powder, DDT.

The school was split in two; lower primary school (småskolen) 1.–4.,

and upper primary school (storskolen) 5.–7. grade. We went to school

for four weeks and stayed at home for four weeks while the other class

was in the school. We travelled by boat. There was only one teacher at the school,

and he taught all the subjects both for the lower- and upper primary

school, except for woodwork and needlecraft. The teachers never stayed

for a long time, most of them only a year.

(Olav Isaksen's story, SSH-3)

|

Kokelv school 2006. (Photo: Svein Lund) |

– I knew both Sami and Norwegian when I started school in the

boarding school in Kokelv in 1962. We were three children who spoke

Sami. The others came from small villages in Revsbotn. We used to speak

Sami together, but we had to do it secretly, because they denied us to

speak Sami both in the dormitories and in the school. Since I spoke

both Sami and Norwegian from the beginning on, no one could tell from

my Norwegian that Sami was my mother tongue.

– Both in the school and in the dormitory it was awfully strickt. We

were not allowed to go out to play with the other children, we children

in the boarding school were to be kept separated. We got very bad food,

every night they served oatmeal porridge, and dinner was most often

salted herring. How intensely we hated that salted herring! In the

basement of the dormitory there was a huge barrel of salted herring,

and once we boys destroyed that barrel. Although the fjord was full of

fish we rarely got fresh fish. I have one particularly bad

memory. There was a barrel of diesel in

the furnace basement. Once the diesel flowed

into the food basement and onto the sacks of oatmeal. Still they made

porridge out of that oatmeal and we had to eat it.

The house keeper was not quite good, to put it politely. I

vividly remember how when we played she would come and tell us: – You

are like wild indians. And when we kept still she would complain that

we did not do anything. We did not know what to do, because everything

we did was wrong. My cousin worked as assistant in the dormitory. But

she was under the command of the house keeper as well.

We boys had to fetch milk and food for the school, among other things we had to pull the fish on a sledge from the fish factory. It was very far. And that kind of work had to be done in all kinds of weather.

In the dormitory there was a kitchen, a dining hall and a room for playing. We boys lived downstairs and the girls had bedrooms upstairs, we were not allowed to go up there. We had one teacher who lived at the end of the dormitory, otherwise the teachers never came to the dormitory.

In 1962, 18 years old, she were to return to Grensen

boarding school where she had spent some of her early years. A lot had

changed - among other things there was more cold cuts for the

sandwiches. But the practice of giving the teachers who worked at the

school better food than the pupils was still the same as when Anne

Kirsten was there as a child.

- The table was set with a white tablecloth and it was served well

for the

teachers. They always got the best food, and often something extra in

comparison to the students, Anne Kirsten tells, and adds that the four

years in

Grensen boarding school was nice and included a lot of time spent

together with the children.

Here you find all the articles in the series:

28.09.2007 Why Sami school history?

05.10.2007 Boundless ignorance

12.10.2007 Southerner-teachers encounter the Sami language

19.10.2007 The start of Sami beginner instruction

26.10.2007 The start of education in reindeer-herding

02.11.2007 From Sami to Norwegian vocational training

16.11.2007 Struggle for Sami gymnasium

28.11.2007 School experiences of Norwegian speaking Samis

14.12.2007 Resistence against Sami language and culture

25.01.2008 A strange world

23.05.2009 On Sami teachers

30.05.2009 Life in boarding school

06.06.2009 Sami pupils were bullied

13.06.2009 Sami content in the teaching

20.06.2009 Pupil as interpreter

04.07.2009 How the children quit speaking Sami

10.09.2010 God does not understand Sami

08.10.2010 The point of view of the Norwegianizers

13.10.2010 Men of the church defending the Sami language

02.12.2010 Sami teachers in old times

09.12.2010 Boarding school life in old times

18.12.2010 Sami pupils in special schools

14.01.2012 The parents' struggle for Sami education

21.01.2012 Reluctance and absence

28.01.2012 The school during the war

04.02.2012 Reconstruction and barrack schools

11.02.2012 Curriculums - for Norwegianization and for Sami school

18.02.2012 The great struggle of the curriculum

Sami school history 1

Sami school history 2

Sami school history 3

Sami school history 4

Sami school history 5

Sami school history - main page