Sámegillii

Sámegillii  På norsk

På norsk

Articles about Sami school history

Part 21 - printed in Ávvir 09.12.2010

Do you know Sami school history?Sámi skuvlahistorjá / Samisk skolehistorie (Sami School History) is a series of books published by the publishing house Davvi Girji. In about 200 articles in 5 volumes there is told about the experiences of Sami children in Norwegian schools, and about the changes in the educational politics of the Norwegian authorities towards the Sami population. The books are published with parallell text in Sami and Norwegian language.In this web site some of the articles of the first book are also published in English. It would be too much to translate it all, so to make this history available to a greater public, we are translating a series of newspaper articles, which sorted by topics make a summary of stories in the books. So far there are 28 articles published in Sami language by the Sami newspapers Min Áigi and Ávvir. They are also published here in Norwegian and the English version will be published gradually as they are translated. These articles are edited by the main editor, Svein Lund. Besides him the editing board of the book series consist of Elfrid Boine, Siri Broch Johansen and Siv Rasmussen. |

A great part of the population in Finnmark have lived in a boarding school for 7-9 years. The first ideas to build boarding schools arose already in the end of the 18th century, but was not carried out then. The first municipal boarding schools were built in the 1860's at the coast of Finnmark. These boarding schools were usually small and poor. Little has been written about these boarding schools. Following is the oldest story about a boarding school that we have been able to find.

Per Erik Saraksen was pupil in Vestertana from 1909 on. He later became teacher and in 1970 he told the Sami radio about his experiences in the boarding school:

The school in itself was not much different from other small school houses in Sami areas at that time. What was different in Vestertana, was the dormitory in the attic for the children who lived far away. It is also the situation of the children who lived far away at that time, when I did my mandatory 7 years of elementary school, that I will tell you about. ...

The school house was about 9 metres long, the classroom 5 by 5 metres. In the other end there was a chamber for the teacher and an even smaller kitchen. The attic was separated in three rooms. In the middle there was a small hallway. From the hallway in school there was a ladder leading up to the attic. On each side of the attic-hallway there was a room for the dormitory children – one for the girls, the other for the boys.

The attic had a slanted ceiling, which went almost down to the floor on both sides, there was only a layer of timber in-between. In Norwegian it was called "the flatfish attic". On each side-wall there was panelled in a dark room which was a metre wide. In each sleeping room there was a small windowpane. The joists in the attic were made up from a quite round kind of timber with no panelling below, and «tent poles» which had been shaped by axe. Naturally no coatings had been wasted on the attic. In each of the rooms there was an oven with two holes for cooking. Small boxes for firewood served as benches, and in addition we had our own food chests. ...

This was Tana municipality's cheap dormitory solution.The municipality provided firewood and light, but all the rest had to be provided by the parents. We used to bring provisions: Bread and Sami cake, butter, pieces of half-dried meat, a keg of cultured milk, a small tub of salted fish and a bottle of cod liver oil.

The municipality did not pay any staff for these children, not even someone to clean the floors. We had to do everything ourselves. In my first year of school we were only two 8 year old boys, me and Simon Mortensen, from Šuoršjohka (Sjursjok). We became good friends and it went well. The lower primary school lasted only 5 weeks in the early autumn and 5 weeks in the late spring back then. More boys came in the years after.

Each of us used to bring bedlinen, shoe grass (Carex), a plate, a cup, a spoon, a table knife and a washtub. Some also had a water bucket and a small pot.

For each turn of school we arranged who would cook in the same pot. Each sliced a piece of meat and put it into the dinner-pot. The meat was marked with cuts, thread or small wood chippings to recognize the owners of the different pieces of meat easily. Once we had finished eating, we normally put our cutlery unwashed back under the lid of the chest.

We had to get water in buckets a couple of hundred metres from the house. In the winter it was difficult and tough for small children. None of us had a watch. We fell asleep when we got tired and woke up when the caretaker began to light the oven in the class room. In the winter when it was frost there was a thick layer of ice on the top of the water bucket in our room. Those mornings we were allowed to come in to the classroom to get warm by the oven before the school started. (SSH-4)

|

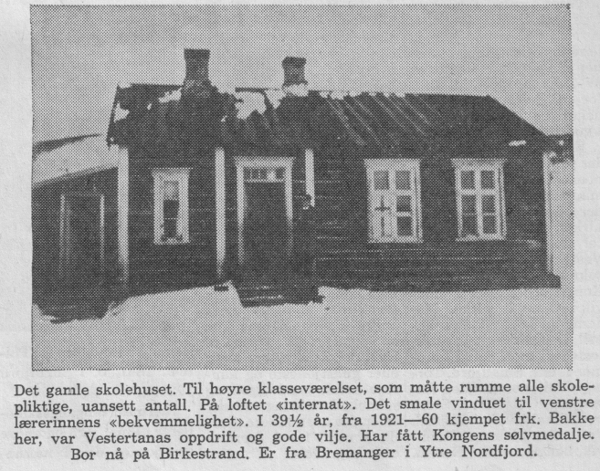

The old boarding school in

Vestertana, 1926 Photo from the magazine Jul i Tana 1961 Right: The "new" boarding school in Vestertana |  |

In 1899 the decision was made to start constructing governmental boarding schools in Finnmark. It was clear that the boarding schools should not only ensure education of everyone, but also serve as an important tool in the process of Norwegianizing. Some argued eagerly that the boarding schools should not only enlighten the children, but also the grown ups in Finnmark. This is how Bjarne Hofseth wrote in his book Finmarkens fremtid (The future of Finnmark) in 1920:

Until now it has been far more difficult for children and young people up here to develop their abilities compared to children and young people elsewhere.

Yet the enlightenment system is in a pleasant development. The primary school boarding schools in particular is an institution of an extraordinary far-reaching impact, but they are only operating in the districts with the most scattered settlement. Here children from all kinds of homes come together — it educates to community spirit, which is what the society in Finnmark is lacking the most. The teaching is only one part of the matter. The personal influence of the teacher is of an even greater importance, and it is pleasant to see how high the quality of the new generation of teachers in Finnmark is.

Well equipped, energetic men and women work as teachers in the elementary school. In part people from Finmark, in part people from outside. But the people from outside among the teachers often seem to take root in Finmark and they often enter the life of the people as if they belonged here. Thus they function as a highly valuable sourdough among the population.

Apart from the influence of the teacher and the teaching, in the boarding schools the children enter a well ordered household and the influence of a selected housekeeper, which is also of great importance.

Through the stay in the boarding school the child is given valuable impulses, but when they return home, where the conditions are far behind, what has been gained is often lost again. Yet the boarding schools indefatigably plant good seeds, although some fall on stony ground and some dry up.

The boarding school is only a 10 to 20 year old institution, but it already seems to be proven that a boarding school will be a valuable, though modest, cultural centre in it's district. Given that the development continues in the same direction as it has until now. The selection of people is very important, both concerning the central management, as well as the singular employees in the boarding schools. The knowledge that the teaching at the boarding school spreads is in fact not the chief concern — that is also received at the common elementary schools. But the personal influence the boarding school employees have for the children, and in part also for the grown ups in the district, is the exceptional value. While a common teacher is only a private individual, which is only working in his personal value, the boarding school employees grow together with the boarding school and the enlightenment system as their glaring representatives. The official position grow together with the person to a quite different extent — and the effect becomes far more profound.

It would be a fortune for Finnmark if this institution grows to be big, and if one continuously is able to obtain worthy employees. (SSH-4)

|

Kårhamn

boarding school (Photo: Bernt Thomassen / The photo collection of Ulf Jacobsen) |

Before the Second World War there were built 22 governmental boarding schools and 28 municipal boarding schools in Finnmark. The governmental boarding schools was normally bigger and the buildings better than the municipal boarding schools. Kårhamn boarding school in Sørøysund municipality was among the governmental boarding schools. Emma Johannessen, who was a pupil there 1934-41, tells:

– We had a 3-floor boarding school. The girls' room was a lot bigger than the boys' room. The girls slept on the upper floor, the boys in the middle floor. The boys had their room next to the housekeeper's room. When they started bashing about, they were scolded of course. Well, the boys were a little bit mischievous. They hung the water-bucket over the door. When the housekeeper entered, the bucket was naturally emptied. But the girls were well-behaved.

There were two classrooms; the lower primary school room and the upper primary school room. In the lower primary school we went to school four weeks at a time, in such a way that when the 1. and 2. class was in school, the 3. and 4. class was at home. During those weeks we did not go home, but stayed in school all the time. In the upper primary school we spent six to eight weeks in school at a time. (SSH-4)

Here you find all the articles in the series:

28.09.2007 Why Sami school history?

05.10.2007 Boundless ignorance

12.10.2007 Southerner-teachers encounter the Sami language

19.10.2007 The start of Sami beginner instruction

26.10.2007 The start of education in reindeer-herding

02.11.2007 From Sami to Norwegian vocational training

16.11.2007 Struggle for Sami gymnasium

28.11.2007 School experiences of Norwegian speaking Samis

14.12.2007 Resistence against Sami language and culture

25.01.2008 A strange world

23.05.2009 On Sami teachers

30.05.2009 Life in boarding school

06.06.2009 Sami pupils were bullied

13.06.2009 Sami content in the teaching

20.06.2009 Pupil as interpreter

04.07.2009 How the children quit speaking Sami

10.09.2010 God does not understand Sami

08.10.2010 The point of view of the Norwegianizers

13.10.2010 Men of the church defending the Sami language

02.12.2010 Sami teachers in old times

09.12.2010 Boarding school life in old times

18.12.2010 Sami pupils in special schools

14.01.2012 The parents' struggle for Sami education

21.01.2012 Reluctance and absence

28.01.2012 The school during the war

04.02.2012 Reconstruction and barrack schools

11.02.2012 Curriculums - for Norwegianization and for Sami school

18.02.2012 The great struggle of the curriculum

Sami school history 1

Sami school history 2

Sami school history 3

Sami school history 4

Sami school history 5

Sami school history - main page