Sámegillii

Sámegillii

På norsk

På norsk

Article in the book Sami school history 1. Davvi Girji 2005.

I came from Oslo to Kautokeino just after finishing upper secondary school and school of home economics in 1953. We were five teachers with no teaching education, the youngest was 17 years old. That was Ole K. Sara, who was a substitute for a short time. Four of us were below the age of 21 and didn't have the vote. Ole was the only one who spoke Sami. The educated teachers at our school were Ola Aarseth, Alfred Larsen and Anders Bongo. All of them spoke Sami. Right away I understood the necessity of trying to learn Sami in order to function as a teacher. Many of the pupils didn't know much Norwegian. I never heard that it was forbidden to speak Sami in school, and was quite surprised when I learned that many, many years later. I've asked other Norwegian speaking teachers who have been in Kautokeino, and they all say the same.

My first teachers were my pupils. In the announcement for the job I applied for, it was told that one was obliged to attend a Sami language course. I asked for this course and the answer I got was that the announcement was to be understood in this way: If there was a Sami course, you were obliged to attend, and if you demanded it, they could start a course. An arrangement was made, and the parish pastor Jan Harr did a course for us three Norwegian speakers. Back then, as now, the priests were required to learn some Sami when they were posted in a Sami district. We learned some grammar and necessarily a few words in the process. We also got a crash course in cursing, so we could tell when the children were using foul language.

My best teachers were my Sami friends. I learned while we cut shoe grass (Carex), did handicrafts, sang hymns together, went fishing and drove with reindeers. I learned some Sami by reading the Bible, where I knew some of the texts. My bedsit was very cold when I got home from school, so I sat by the oven with all my clothes on and read while it was heating up. To light the fire with "Svalbard coal" is a craft, which I didn't quite master.

The nomadic Sami children knew Norwegian quite well. They had school some weeks before Christmas and went home for Easter. It was more difficult for the permanently settled. Those children often knew specific sentences and expressions perfectly, and it was easy to overestimate how much they actually understood.

The children had to learn hymns by heart. For the sake of appearances I had to learn the same as the children. I've discovered quite a few grammatical oddities by reading hymns. The Bible and the hymn book were good textbooks, although the language didn't quite follow the norms of everyday speech. In addition you heard Norwegian speech interpreted to Sami in all church services.

In the first grade I taught using Margarethe Wiigs Sami/Norwegian ABC (primer). Some have said this book has never been used for teaching in schools. That's not correct. It was in use for several years in Kautokeino. Apart from that the language of teaching was Norwegian and lots of drawing on the blackboard. Margarethe Wiig was forced to use two languages in her book. That's why it was difficult to learn from it. Afterwards Norwegian books were used for beginners for many years.

Teacher Liv Johnsen (later Jerpseth) was the first one I heard mentioning the need to produce a new primer in Sami. She had a basic Sami university course and was a speech therapist. The two of us travelled to Kiruna to professor Hansegård, who was working with bilingualism, to hear his opinion. He encouraged us to get started. Liv sent a letter to the Ministry of education offering to write the text, and I would make the illustrations for a Sami ABC. We got a response saying that Inez Boon already had started working on such a book. But I was offered the job of illustrating this book.

At the time beginners' teaching of Sami was established, several short Sami courses were held for the teachers at the school.

People were always very positive and understood everything for the best. They praised and encouraged me, as they also do in child rearing in Sami areas. If I had been criticised too much, I think I would have stopped speaking pretty soon. But the price was quite a few established errors.

I discovered that once you started to know the language, the demands were high. I barely dared to speak Sami to anybody other than my old friends. I've experienced, as probably speakers of Sami language always have experienced, that you need courage to express yourself in a different language when you're insecure. It's embarrassing to say something completely wrong, and I've heard the blunders of Norwegian speakers repeated and laughed at for years.

The best way to correct the language is to repeat the sentence correctly. Inga Laila Hætta was very good at that while we were working together at Sami Education Council. At the same time she gave a lot of praise and encouragement. She was the one who corrected the worst errors when I started to make easy to read books in Sami. Otherwise my books were praised because they had such a simple and childish language. There is some use in not knowing too much after all.

I'll tell a bit about how I experienced doing special teaching in Kautokeino. First some history. Pupils with special needs were in regular classes, often just sitting there, without any special help. Not until many years later, in the 70s, did some of these pupils get some teaching as grown ups, at the family/daycentre in Kautokeino. This teaching was directed by the elementary school. When I came to Kautokeino in 1953, they had school in the autumn and spring for the children who were living there permanently and school in the winter for the nomadic Sami children. In order to get as many hours of teaching as possible in the short period the children were at school, the primary school had five hours of teaching every day. I remember having to give some supplementary teaching after the fifth lesson. Poor children! This was while we still were in the school barracks.

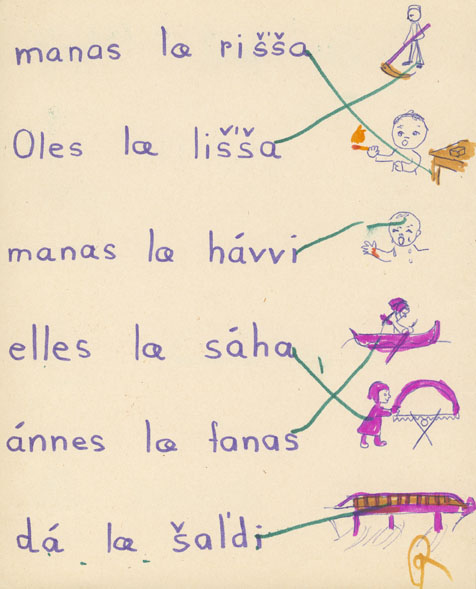

| In the special-class the teachers mostly had to make the teaching materials themselves. This is from a workbook Inger Seierstad made and a pupil has filled in.

|

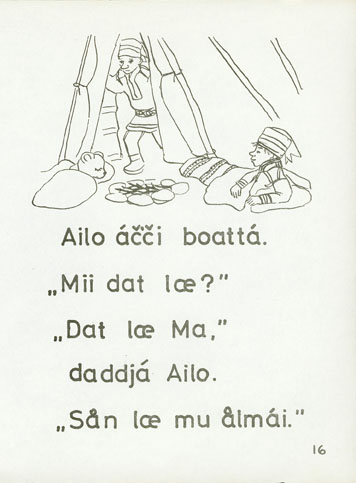

The inspectors were probably shocked. At least I was offered the possibility of siting in on classes at a special school at Sørlandet. I did. They made a lot of the teaching material themselves there. I was encouraged to write "Má ealu luhte". I think it's the first book aimed at special teaching written in Sami language,

| The first book for special teaching in Sami, and the only one to be published with the old orthography, was Má ælo lut'te, where Inger Seierstad was responsible for both text and illustrations.

|

After some time I got a group of pupils with learning difficulties. At the time I did further training at Eik teacher's college. When I started, it was called "primary school pedagogics". During the course of the year the course was approved as 1st course of study in special pedagogics. Consequently I had the right of leave with salary, since I came from a Sami district. This was in 1970. We learned a lot about basic reading-, writing- and arithmetic - teaching, naturally intended for Norwegian schools. This was something we had barely touched on during two years of teacher's college. Otherwise we learned just about the same as other students who did the 1st course of study in special pedagogics. We had to have a book in English in the curriculum, so we learned about dogs, rats and worms and how they learned.

The previously mentioned pupil had some lessons with Lise Bamrud Øien at first. She was speaking Norwegian, but had been teaching at a special school for a couple of years. After a while it became a group of pupils, for whom there was an application for extra funding. Their teacher was Eldrid Aksnes. Later I assumed responsibility for the group.

After a few years the group became a special-class, after a formal application for these pupils. The special-class existed from the beginning of the seventies to the beginning of the eighties. I was the form master.

When the special-class was established, the school had a speech therapist, Eldrid Aksnes. She had lessons with those who needed it. She had been teaching some of the pupils already before they started school. She understood some Sami, but felt it was too little for her to be able to work efficiently. When she quit in 1974, the school looked for a Sami speaking speech therapist. There wasn't more than one at the time, and she already held a permanent position in Karasjok. There was one applicant, but she only spoke Norwegian. And when she didn't get a permanent post, she withdrew her application. After that the speech therapist position in Kautokeino primary school was suspended.

One of the teachers who spent the longest time in the special class was Idar Andreassen. He came from Romsdal. He came to Kautokeino in 1965 and after some time he understood a lot of Sami, but spoke little. He finished his education in special pedagogics in 1972, and shortly after he came to the special-class. Idar was our jack of all trades. He fixed all kinds of technical apparatus. He could glue together our rocking chair and expand and weld together the tricycle so that the bigger children could use it. Several of them needed to learn to move as much as possible.

We also had an assistant, Maria Anna Eira, for many years, until she retired. We all called her "Ánne-goaski" (Aunt Anne). She had her knowledge from a long and variable life in the reindeer herding environment. She was an invaluable helper and must have had natural pedagogical gifts. She raised us all wisely, both teachers and pupils, with stories and warnings in a fine and nice way. She was good at praising and encouraging. In addition she taught us to cook Sami dishes. She was also a good language model for all of us.

We got more pupils down the years. Some came from the family/daycentre, where they attended during the day. When they reached school age they came to the school some hours every day. There were multi-handicapped children, with no ability of speech. We established a special-class with younger pupils too. At first I was their form master too. Later Anne Guttorm from Karasjok became their form master. She is educated in special pedagogics and Sami is her mother tounge. Ánne-goaski was assistant in this group too.

| From the special-class; Ánne-goaski and a pupil.

(Illustration by Inger Seierstad) |

When it became two groups of pupils, we had two more rooms on the first floor in the old dormitory-wing. These two rooms also had new tables and chairs. Otherwise there was a lot of floor space and mattresses on the floor. The rooms of the two special-classes were just across the hallway from one another.

The rooms had a lot of cupboards, since they had been bedrooms previously. The rooms and cupboards were well used - boys had been living there. But we had everything we needed. When I think about it now, when it comes to material resources it was like paradise compared to the schools today.

There was a separate budget for the special-classes. We could buy nearly everything we wanted, if we found it useful for teaching. After some time we had wall bars, a swing, a bench for balancing and several different toy devices. We got our own film projector, screen and an "instant-camera". Otherwise we naturally had access to all the facilities in the rest of the school. We had two xylophones, drums and other kinds of percussion. We had all the arts and crafts materials we wanted.

We had a lot of books, and also our own budget within the school library. The only problem was that the books were in Norwegian. There were very few children's books in Sami at the time. But we made use of them anyway, by using the pictures and having the teacher tell the stories in Sami. The pupils weren't able to read themselves. The most difficult part was when the settings of the stories were too unfamiliar.

What I enjoyed with the special needs class was that we were able to plan the teaching and adjust it to each pupil. I made use of what I had learned of arts and craft and music. And there were good opportunities to use fantasy and creativity.

Only later did we have some reading and writing in Norwegian. Since one of the teachers was speaking Norwegian, some of the teaching was done in Norwegian. Afterwards some of the parents felt that their children would have done better in the greater community if they had learned more Norwegian during their childhood. Then they might have been able to make use of offers in special schools, which still existed back then.

I predicted we would have problems when the new Sami orthography was introduced in 1979. But the transfer took place with surprising ease. I think that indicates that the new orthography really is easier to learn than the old one.

There weren't any suitable textbooks in Sami, so the teacher had to write the books for each individual. That's something all special needs teachers have experienced. These hand-written books became the foundation for the later "Muorje-girjjit" [1] I made them with special-teaching in mind, but I know they have been used in many other contexts. I'm not all happy about it, because they're not suited for all kinds of teaching. Among other things they have been used for teaching Sami to Norwegians. They're of course not meant for that, but it shows the great lack of Sami books.

Apart from that we had all subjects like the other school children. Idar was an outdoorsman, and spent a lot of time in the nature with the pupils, and taught them about the things they saw and heard there. He showed them "palser" (tussocks) with ice inside, which they could use as refrigerators. They learned a lot about birds, and every pupil had his own bird, which he specialised in. They were few enough to fit in a car. I remember them setting out nets one day and drawing them in the next. Afterwards they cooked the fish at school. Idar taught housework too.

We made cookery books with drawings and no text. We cooked the same dishes many times. An important part of the teaching was to do grocery shopping. We tried to consider what the pupils would need to know after they finished school.

The camera was used to make a memory book, and to find out if anyone bothered our pupils. The pictures were also used to make a "recognition book" with pictures of things in our local environment for the weakest pupils.

The arts and crafts assignments had to be simple. But it wasn't a problem since we had plenty and varied materials. Some of the products were real works of art.

We had a lot of music. Everyone was together. A lot of the pupils in the special-class were very musical. I'm sure they knew a lot more hymn- and song-melodies than any others at their age.

All in all there were 14 children in the special-classes when they existed. A couple of them were only there for a short while. Some got all their elementary schooling there, and continued three years in upper secondary school with adjusted teaching. Some went to elementary school in the special-class and were "integrated" when they started secondary school. It seemed like most of them liked it at school, and we had very little absence. As a teacher I have to say that it was my best and most joyous time in school. Not all teachers get the privilege of being greeted by a big smile every morning or get to hear that: "school is fun" every day. I've also talked to grown up pupils who express that the time in school was good.

The ones who had a difficult time were the ones who functioned closest up to "regular level". It would probably have been better for them to be in a regular class. They didn't stay that long in the class either. The differences between the pupils in the special-classes were greater than between the other pupils in primary school. The ones who functioned well were afraid to be identified with the most handicapped.

We made a few tries on having our pupils in the regular classes for some lectures. It didn't work out very well. Maybe we were too much on our own. We participated in the joint activities of the school. Most of the children were outside in the breaks at the same time as the other children, but not all. When we celebrated something, and we often did, the pupils were allowed to invite one guest each. They rarely chose children, not even siblings. They asked the principal, the school leader, priest and other teachers, and they came. The parents were obvious guests, as far as they had the opportunity to come.

We tried to keep contact with the parents, and most of them showed the teachers great trust. I was afraid they'd believe we could do more than we were actually capable of.

We had regular contact with the pedagogical-psychological services in the municipality, and also to an "audio-educationalist" and other specialists. Students were some times sent for shorter stays at different special institutions. Usually they wanted a Sami speaking teacher to be there while the pupil was there, because at the time no one had competence in the Sami language in these institutions. Sometimes the teacher also had to follow the pupils to doctor or dentist outside Finnmark, if the relatives couldn't do it.

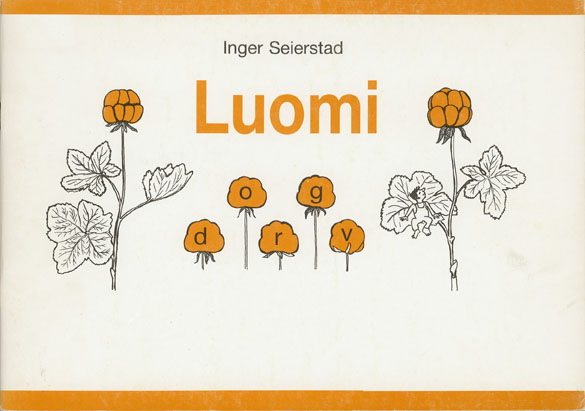

| Among the many books Inger has written and illustrated are Muorje-girjjit (The berry-books): Jokŋa (lingonberry), Luomi (cloudberry), Sarrit (blueberry) and Jeret (redcurrant).

|

I've lived to see my pupils as grownups. I've followed the pupils of the special-classes. I know the ones who has been "integrated" both before and after the special-class existed.

In my view the differences between the pupils who went to the special-class and the ones who went to a regular class are very small, when it comes to how they function in the community now. How much they participate in the regular community life are depending more on their different personalities and how their surroundings make the conditions favourable, than where they had their schooling. One of the arguments against having special-classes was that the pupils would be isolated from the environment they would live the rest of their lives in.

The pupils in one of the special-classes had both Norwegian speaking and Sami speaking teachers. As grownups they speak and understand both Norwegian and Sami, at least they manage well in the everyday life. I'm actually surprised at how bilingual they are at their level.

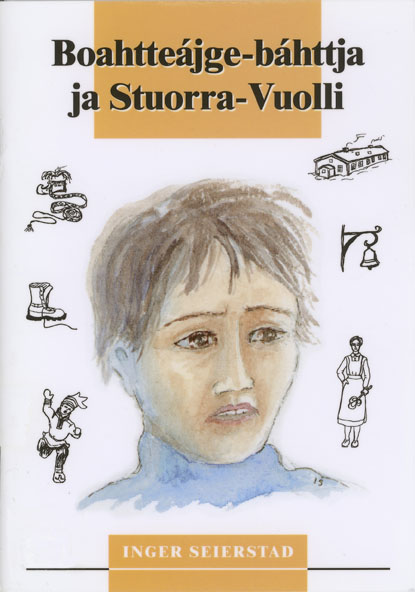

| The three books about Boahtte-áigge-bárdni (the future boy) tells the story about a boy of our time who ends up in a boardingschool 50 years ago. These books are also translated to Lule Sami language, which is shown here.

|

[1]

[2]

More articles from Sami school history 1