Sámegillii

Sámegillii

På norsk

På norsk

Article in the book Sami school history 1. Davvi Girji 2005.

This is a subjective account of a Norwegian's experience of the Norwegian school in a Sami community in the 1960- and 70s.

My sister was a teacher in Karasjok at the time, and maybe that contributed to motivate me to go to Samiland. I found it important to know the mother tongue of the children to be able to do a good job. Therefore I tried to learn a little Sami on my own while attending the teacher's college in Volda. But I only had written sources at hand. To prove that I knew some Sami I wrote the application to the school board in Porsanger parallel in both Norwegian and Sami. It created more stir than I had reckoned, so the rumour went ahead of me to Skoganvarre: A teacher who was a southerner and spoke Sami was about to come.

When I had presented myself to the pupils in the first lesson and we went out to have a break, one of the older boys came over to me and asked me forthright in Sami: "Mo dat orru?" (What do you think?) I had barely heard the language before, until then I had only seen it written, and he probably hadn't seen his mother-tongue written, so the conversation was slow in the first try, to put it mildly. Later I got the opportunity to prepare, and got a lot of praise for being so good at speaking Sami. It was nice in itself, but it was so to speak impossible to give compliments the other way, and tell someone that they were good at speaking Norwegian. I think many would have found it embarrassing, maybe even degrading. After all we were living in Norway, and it was probably unusual that we didn't all speak Norwegian!

A pupil and a good friend had the honesty to put my Sami knowledge in the right perspective: We were some acquaintances who were sitting and talking together, partly in Sami and partly in Norwegian, when my good friend, who considered himself as Norwegian speaking, blurted out: "I know Sami. I understand everything. But I don't dare to speak. But Sverre Hatle, he dares to speak Sami, although he can't!"

My colleagues in Skoganvarre were the married couple Birgit and Richard Bergh, who worked there from the school was established in 1962 and up until 1969. They didn't speak Sami themselves, but supported me fully in my project. They were passionately committed to making the children in Skoganvarre, both Sami and Norwegian, able to gain status and self respect like everybody else. And they knew at least as good as I did how difficult it was to teach Sami-speaking children using curriculums and textbooks which presupposed that their mother-tongue was Norwegian. Richard Bergh was an eager collector of folklore, and through this work he made close ties to the villagers in Skoganvarre and out along the Porsanger fjord.

The prevailing opinion in the school environment in Porsanger was that Skoganvarre was something of it's own, the Sami element was strong here, no-one could deny that, and it was accepted that the teaching had to be specially adapted. At the other schools, on the other hand, all of the pupils spoke Norwegian. As I got to know the commune, I realised that this was only partly true. Some teachers also admitted then that it happened that some children started in their school without being able to speak Norwegian.

I knew that I couldn't come to Porsanger and introduce Sami as the language of teaching. I were careful not to speak Sami to anyone in the lessons, but in the spare time and breaks the conversations often were in Sami. After some time Sami became accepted in the school yard. But it might have been just as related to the fact that the part of Sami-speaking pupils were increasing.

I vividly recall a student from a different school in Porsanger who came to Skoganvarre in an errand. In a break he got into a conversation with some of my pupils, and I noticed that they were speaking Sami. When I came over to them and spoke Sami he was probably very surprised, and he blurted: "Lea go skuvllas lohpi sámegiela hállat?" (Is it allowed to speak Sami in the school?) I asked him rhetorically where he had heard that it wasn't allowed, but I didn't get any clear answers.

Samuel had started in the upper elementary school (4.-7. grade). I think he was bright, but he had probably knocked his head against the wall many times. He confided me that the first years of school had been hard. "But when I started the third grade I started to understand what the teacher was saying, and then it became a bit fun!" But the school was probably still a strain. We had a math test one day, Samuel handed it in very early. I didn't think he had put any effort into it at all, so I made him do the test again. I saw tears in his eyes, but determined he threw himself into the work. A sharp, clicking noise was heard from his desk while he was working. After he handed in the test the second time I saw that his "gum" was left at his desk. It was a tin button from his knitted jacket which he had chewed until it was a compact lump!

Samuel and I became good friends. Together with a group of other students -especially the ones who were lodged with hosts in the village - he came to visit me in my bedsit several evenings a week. They sat there and talked and yoiked. I had a recordplayer and the first yoik record of Áillohaš, it was played again and again.

The last day of school before Christmas we were going to have a service in the chapel and a nice gathering, and the school wasn't supposed to start before ten o'clock. I was planning to sleep in that morning, but already around seven o'clock a group of students had gathered in the school yard, outside the window of my bedsit and were yoiking at the top of their lungs in giddy and true joy. They kept it going until ten o'clock.

Per-Heika didn't do very well at school. One could call him a looser. Only reluctantly did he put on his national costume to go to Lakselv 17th of May and walk under the new Skoganvarre banner. He would rather go fishing on the ice. Many years later I was travelling with the Nord-Norge-bus from Alta. Somewhere on the mountain between Skáidi and Olderfjord a young man dressed in the national costume walked on the bus. Clearly he came from the reindeer herd. I recognised him, and he saw me. Determined he walked to the rear of the bus and took my hand: "Bures!" It warmed the cockles of my heart, and I was happy that we met there on the mountain as equals, grateful that the school hadn't taken away his dignity and self-respect.

| Skoganvarre school in winter dress - even if it's summer! It was a snowy weather the 14. June 1966, which made the lawn white for a while.

(Photo: Richard Bergh) |

Inez Boons textbook series for reading and writing education in Sami was published in 1967: the books about Lásse ja Máhtte, just as Liv Jerpseths arrangement for verbal teaching in Norwegian as a foreign language, and the first classes of Sami beginners education was started in Karasjok and Kautokeino. Already the following year we got the request in Skoganvarre if we wanted to offer new pupil this arrangement. It was impossible to turn it down, although we didn't have any teachers with Sami as the mother tongue.

It was emphasised that the arrangement was voluntary, the parents should choose. Hans Eriksen, consultant for the superintendent of the school, came himself and did a round visiting the parents together with me. We started Sami beginners education in the autumn 1968 with two students, which were 50% of the first graders. Finally Sami was recognised as the language of teaching, but after about one and a half year the teaching was supposed to continue in Norwegian.

As far as I can remember the reasons given for offering Sami beginners education was consistently that the pupils should get better in Norwegian, never that it had a value in itself to master writing in the mother tongue. I reckoned that this was a strategy chosen in order not to provoke. If someone tried to argue that the mother tongue was an important instrument for the child, the objections arose quickly: "Gosa dainna sámegielain?" (Where will this Sami bring you?) But I thought to myself that the knowledge of Sami would come as a side-effect.

The arrangement didn't meet much resistance. After all the strategy of voluntariness practically rendered open resistance impossible without exposing the prejustices. But it evoked discontent that the class with Sami beginners education didn't come in additionto the favourable class division the school had before. It was a crude and unrighteous assertion that the Sami beginners education "was detrimental" of the Norwegian pupils, but it became a persistent myth. To remind of the injustice the Sami pupils had suffered through generations was useless in this context.

I and my two pupils did our things unaffectedly. We were doing a pioneering work, but we weren't doing any unusual things at all. The unusual was that a teaching arrangement like this didn't get started before the late 1960s in our enlightened country. I also taught Norwegian as a foreign language, although it was recommended to use a different teacher in Norwegian. I didn't feel that it was a problem. The puppets Lise and Ola were effective signals that everybody had to speak Norwegian. It was respected fully, but when the Christmas was approaching, one of the girls wanted to take Lise and Ola with her home for the holidays in order to teach them Sami, so we wouldn't have to speak Norwegian in the new year.

I knew that there was a lack of Sami teachers, and that the few who existed had a lot of tasks calling for them. I thought that it wasn't time to ride hobby horses, but to get things done. So I accepted the enquiry on the condition that my proposition would be presented to a representative forum of teachers who were teaching in Sami. The primary school council appointed a "reference-group" which I met with on a regular basis, and consulted while working on the proposition.

The framework was tight: The curriculum for Norwegian with calligraphy were to be worked out first, and the Sami curriculum were to follow it's patterns.

I admit that this felt like wearing a straitjacket and an underlining that we weren't dealing with two equal languages, but who doesn't swallow a camel if it can speed up the desert journey!

Inez Boons beginners publication consisted of three textbooks: lás’se ja mát’te ruovtos

I got support for my view, and in the end the primary school council asked me to make suggestions for changing the text. These were first published as separate papers with text which the teachers had to cut and glue over the text in the books. It was very difficult to get the methodical guidelines into shape with a system like this.

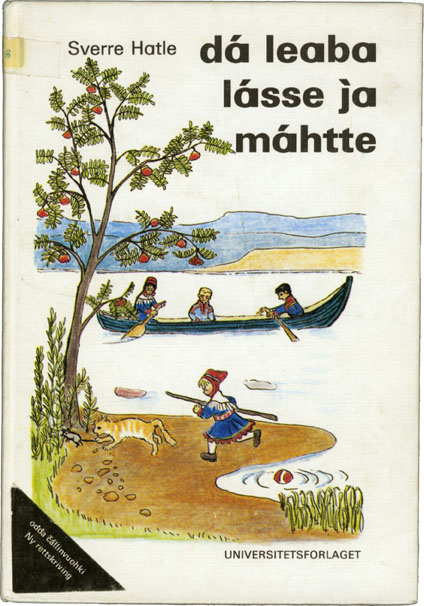

I wanted to change both the two first books, but the primary school council was reluctant. Inez Boon, on the contrary, who disagreed with me on the methodical part, was open-minded and said that we who were using this arrangement, should be allowed to decide what we wanted it to be like. She never put obstacles in the way of the revision. After a lot of pressure, many proposals and compromises a new textbook came into being: dá leaba lásse ja máhtte (at first with the old orthography, later in new editions with the new orthography from around 1980, like all the books I was involved in making). It was supposed to be a revision of lás’se ja mát’te ruovtos, but ended up being a new book for the first grade. Workbook, wall charts of letters and guidelines for teaching were made. Inger Seierstad continued as illustrator, like she had done for Inez Boon's books. (She was originally from Oslo, but had become "Saminized" over the years. From Kautokeino the story goes that a pupil was asked who their "rivgu" (miss, Norwegian woman) was. "We don't have any rivgu", the answer sounded, "we have Inger Seierstad".)

| "dá leaba lásse ja máhtte" was one of the books Sverre Hatle made for the Sami beginners education. This is a newer edition in the current orthography.

|

I though the Sami teachers deserved a good selection of teaching materials, and wanted to make the textbook series extensive, but the primary school council, which had to keep the budget, held back as much as they could. I wanted to write the teachers guidelines in Sami, but wasn't allowed to. The primary school council wanted to control what it said, and they didn't have any Sami competence.

The bureaucrats in the primary school council were people of good will, but they probably had their frameworks to stay within. They were patient with my youthful and un-bureaucratic enthusiasm, and when the Sami curriculum was to be followed up by teaching in Sami upwards the classes, my new assignment was to assist Johan Jernsletten in making the textbook series for 3.– 6. grade, which we called Ginna Galka Borta Snorra. During this work I was on leave from the teaching duty at school.

But the special steps, for instance a special quota with extra teaching resources for dividing classes, was made dependent on the schools being defined as mixed-lingual schools and gave room for Sami cultural knowledge. It was probably a predicament to some schools, because they wanted to "have their cake, but not eat it": as little Sami as possible, but as many "special steps" as possible. Afterwards the extra teaching resources for dividing classes was cancelled by the superintendent of schools, and the "Sami executive officer" got the reputation of being an arch-bureaucratic equestrian of hobby-horses. In Skoganvarre we got what we got what was our right, but it wasn't easy to be viewed as the "favourite child", who got candy and pats on the back, while the older siblings out by the fjord felt they were unjustly treated.

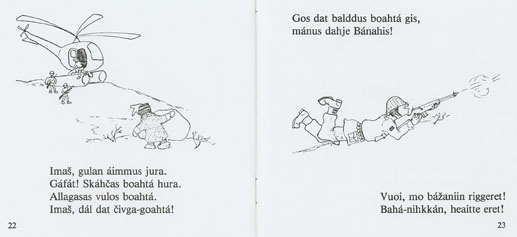

| "Áhkku ja Náhkku" was originally a comic Sverre Hatle made, which was printed in the Sami newspaper "Nordkalotten". It was published later as a book, and became so popular that it was printed again in the new orthography. It depicts two small stallos and their encounters with animals and people, among others they are disturbed by the military, like in these drawings.

|

Well, he was young and naive and a bit extreme, but the notions of cultural contrasts can have different outcomes. I had an old aunt living in South-Africa, where she and my grandfathers brother was running a guest house. In her old days, when the apartheid-regime had fallen into disrepute, she wrote to us: "Don't believe everything you hear about South-Africa!" For generations she had held Sunday school, and was sincerely fond of her small black friends, but the blacks never grew up completely, and it was in everybody's best interest for the whites to rule the country. I met similar utterances in Finnmark in the 1960s, especially when it came to the "mountain-lapps".

Maybe majorities are more inclined to view minorities as different, but sometimes I was struck by how Sami people could exaggerate the cultural differences too. I think some of the people I had contact to on a daily basis in Skoganvarre, had exaggerated ideas about the cultural shock I had experienced when I came from "Oslo or thereabouts". It felt weird to me, who came from the northern parts of the West of Norway, where I had dug in the earth and milked cows in the fear of God and frugality, and didn't find the Laestadians more exotic than the emissaries from det Vestlandske Indremisjonsforbund ("Association for domestic Christian mission, based in the western part of Southern Norway"). At some point someone is supposed to have stated that the cultural differences between Vinje in Telemark and Akersgata in Oslo are bigger than the differences between Vinje and an Indian village. I think he might be right.

The national costume couldn't erase possible cultural differences, but we teachers used the Sami national costume on festive occasions, in the parade 17th of May for instance. I don't know to what extent it was right or wrong. Young Samis today might say that we dressed up in borrowed feathers, but we did it to give the children moral support in coming forward with their identities.

I never considered myself radical, and didn't like to wind up in conflicts with anyone. But the Sami was the humiliated party, and some found it provoking when I claimed their rights. I'm still thinking of how ashamed I was as a Norwegian when a highly respected man in a position of trust threatened to leave a public debate meeting in Karasjok because someone wished to do their address in Sami. He didn't want to be in any circus. This was in the 1970s.

Sometimes principles and ideals have to give way to more important concerns. But when no Sami-speaking teachers signed up for the announced posts at the school, I was very disappointed, and called for the sense of responsibility among the Sami in a contribution in the newspaper Ságat. I insinuated that their own careers were more important to them than the

children's needs.

In 1983 my parents-in-law wanted to hand over the running of the farm and the cowshed to the next generation. From then on I became a farmer.

- With a youth's candour I went north to fulfil my duty to my visions.

- With a father's love I went south to fulfil my duty to my child.

- With a man's maturity I left the school to fulfil my duty to the earth, the fathers and the traditions from which I am arisen.

I'm still thinking like I did back then: The career-ladders in society are turned turned upside down, they should rather go from the ministry, consultant-posts and offices up to the schoolroom or the stool in the cowshed. The work with plans and textbooks were certainly important and necessary, and it can be a nice boost for the self-image to see your name on the book covers, but I probably did the most important work together with Berit, Iver, Anne Kirsten, Lasse and the other children in Skoganvarre. If they're still alive, some of them might be grandparents by now. If so they have a new and exciting challenge in life.