Sámegillii

Sámegillii  På norsk

På norsk

Article in the book Sami school history 1. Davvi Girji 2005.

While Hans Lindkjølen was principal at The sami folk high school he spent as much time as possible in the mountains with the reindeer herding Sami. Here in a lavvu with Marit Kemi. |

Hans Lindkjølen was born in 1923 in Eidskog, Hedmark. He has a major in Nordic, ethnology, pedagogic and religious studies. He has been teacher and principal at the Sami folk high school in Karasjok, headmaster at The sami school in Troms, and teacher, consultant and principal at the primary school in Drammen. While having a leave from the school he got a scholarship from the government to do research on older literature on the Northern Cap and it's peoples. Hans Lindkjølen has published a series of articles and 15 books, most of them are about Sami conditions. Among them are biographies of serveral advocates of sami culture and three volumes on Sami people in literature throughout the ages: Nordisk saga (Norse saga), Nordkalotten[1] and Urfolk i Nord (Indigenous peoples of the North). |

Before the time of the "allmueskole"[2], about 1740, the church were responsible for all schooling in all of Norway. There wasn't an order to establish rural district commissions to rule the school- and poor relief system before 1790.

The first commencements to start schooling for the common people were in North-Møre and in Romsdal. It was the fiery soul of public education, Thomas von Westen, priest in Veøy in Romsdal, who got six other priests in the district to join him in making an effort. They wrote to the king in Copenhagen and told him about the ignorance of the common people. The king responded positively to the enquiery, and the so-called Seven-star-priests became pioneers in teaching reading. The intention was to make the common people able to read the Bible, catechism and other godly books themselves.

The king sent out a decree in 1759, saying that all children were to be confirmed at 14-15 years old, and at the latest when they were 19 years old. In order to be confirmed they had to be able to read. Not all poor children had learned that, and this is where the tragedies appear. They went as far as sending youths to prison until they learned to read.

The ones who managed to run away during the confirmation, lost their social status. The worst part was that they weren't allowed to marry. Not few ran away into the forest and froze to death. This was often an act of desperation of not being able to marry when girls found out they were pregnant.

(Drawing: Josef Halse) |

A lot indicates that the Sami knew of Christianity already before the Reformation, both from Russian, Swedish/Finnish and Norwegian sources, but because they were lacking a written language, Christianity didn't gain much foothold and was mixed with the initial Shamanism.

Among the Sami, as with a lot of other indigenous peoples, the Christian missionaries were the ones to develop a written language. The introduction of Sami language in teaching and preaching started a cultural-political struggle in Norway, which has flared up at regular intervals for nearly 300 years.

The Sami church- and school-history are two sides of the same story. It was in fact the church who undertook to organise the schooling in Samiland. Consequently, developing a written language and publishing books in Sami became a task for the priests and the missionaries. The demand of the Lutheran church that people should learn God's words in their own language lead to missionaries trying already in the 17th century to develop a written Sami language, and some of it were also printed. [3] Already at that time efforts were made to introduce schooling among the Sami in Norway.

King Fredrik IV established the Misjonskollegiet (the missionary collegium) in Copenhagen in 1714, and gave it the task of starting to mission among the Sami in Finnmark. This was started under the direction of Thomas von Westen. In 1716 he established "Seminarium Scolasticum" in Trondheim, and it became the centre for the schooling work among the Sami. Thomas von Westen travelled around in Sami areas several times to start schools and build churches. He threw himself into getting the Sami an ABC-book and other textbooks in Sami. His co-workers translated several books and parts of the Bible, but Luther's Little Catechism were the only to be printed, in 1728, with double text in both Sami and Norwegian. All along bishop Peder Krogh disagreed with Thomas von Westen in wanting the Sami to get education in their own mother tongue.

Knud Leem started to study Sami in 1723, and in 1725 Thomas von Westen sent him to Porsanger and Laksefjord as a missionary. In 1728 Leem was appointed pastor in Alten-Talvik. From the very beginning of his missionary work Leem concentrated on empathising with the Sami language and way of thinking. He wore Sami clothes and talked to people in their own mother tongue.

When von Westen died in 1727, bishop Krogh forced through that all Sami children would get their education in Norwegian/Danish, in order for them to be able to use Norwegian books and participate in church services together with Norwegians. Seminarium Scolasticum was closed down, and the missionaries were instructed to teach the Sami in Norwegian. Not all of them followed these instructions, some continued to follow von Westen's ideas.

New bishops recognised the problem, and in 1752 the "Seminarium Lapponicum" was established in Trondheim. The purpose was to educate missionaries with competence in Sami language and translate books to Sami. Under the title of professor, Leem were appointed manager of the seminary. He stayed there until his death in 1774.

In 1748 Leem published a Sami grammar, and in 1756 a Danish-Sami glossary: "En Lappesk Nomenclator efter den Dialect, som bruges af Fjeld-Lapperne i Porsanger-Fjorden" [A Lapp dictionary following the dialect spoken by the mountain Lapps in Porsanger fjord.] In 1767 he published Luther's Little Catechism and an ABC-book in Sami. Whe Leem died in 1774 he had nearly finished a dictionary in two volumes. The first volume were Sami to Danish and Latin, and the second volume were from Danish to Latin and Sami. The work was finished by Gerhard Sandberg, a missionary in Varanger, and was published in 1781. Leem is concidered to be the founder of the Northern-Sami written language. Two new bishops arrived in Trondheim at this time. They were strong opponents of Sami, and closed down the seminary in 1774.

The same year Olav Josephsen Hjort came as pastor to Kautokeino. Being responsible for the teaching of the Sami in his church he was instructed by the church leaders to ensure that all literature printed in Sami was confiscated. He started his work with no mercy, and confiscated all the Sami printed matter he could find. In the public talk he soon got the name Hard-Hjort.

If the reading skills of the Sami were bad before, it didn't become better after this. Missionaries and priests complained and asked for Sami to be a part of the educational work again.

In East-Finnmark P. V. Deinboll was priest and senior rector in 1816. He continued the work of Thomas von Westen and travelled around in his wide district to get schools started. But all the time the linguistic difficulties was an obstacle. In 1826 the cries for help were followed up, and the first official teacher's college was established at Trondenes. It was aimed especially at educating Samis and others who wanted to work in the Sami areas in the north.

After pressure from the Finnish-Karelian population in the south-east the number of Sami grew rapidly in Finnmark from 1567-1865, according to J. A. Friis. In Sweden, Finland and Russia the number of Sami decreased in the same period. The beginning of the 18th century were strongly influenced by war between Finland and Russia. The Finnish people were impoverished to the extent that nearly everyone who could crawl or walk fled to Finnmark or Northern-Sweden.

The monopoly-tyranny which the merchants from Bergen exercised, through the privileges they had received from the Danish government, reduced the Norwegian population in Finnmark considerably. At the census in 1845 the number of the Sami and Kven population were nearly the double of the Norwegian in Finnmark.

Sami and Finnish were the everyday language of the majority. Consequently the Sami children had big difficulties understanding the teaching which were done in Norwegian.

| N. V. Stockfleth made a big effort for the Sami language, but as a priest he was very stern, and after the Kautokeino-rebellion in 1852 he was among the ones who wanted severe punishments. |

8. April 1846 Stockfleth sendt an appeal to the king suggesting that prospective priests should learn both Sami and Finnish. The suggestion was put forward by the government on 12. February 1848, and passed by the royal decree of 24. February the same year. Stockfleth was himself in charge of the teaching of these languages at the university in Christiania, until J.A. Friis took over the teaching in 1851.

But Stockfleth had his opponents. Pastor Zetlitz was one of them. He had been the prost of Kistrand parish from 1836, a parish which encompassed nearly all the nomadic Sami in West-Finnmark. He saw it as a natural development for all Samis to merge with the Norwegians, and meant one shouldn't make any obstacles to this development.

Stockfleths strongest opponent among the clerical was senior rector Aars in Alten-Talvik. As a representative of Finnmark in the Storting (Norwegian parliament) in 1848 and 1851 Aars made sure that the royal decrees concerning the language and teaching situation from 1851 and 1853 didn't reach as far as Stockfleth and his fellow partisans had wanted. Moreover senior rector Aars strongly opposed the recently passed royal decree of February 1848, where it was adopted that when appointing new priests one should take knowledge of Sami and Kven languages into concideration.

In the years 1841-1843 Stockfleth stayed in Kautokeino for long periods of time. Being the substitute mayor in the absence of prost Zetlitz, he chaired the first meeting of the school commission. In his stories Anders Bær draws a picture of the relationship between the high officials and the Samis which isn't always in Stockfleth's favour. He could act in such a strict and authoritarian way that his military background shone all too clearly through. On a mission from bishop Juell in Tromsø, Stockfleth travelled to Kautokeino in October 1851 and stayed there until April 1852. His mission was to try to lead the Laestadian revival movement [4] in to a good direction. He gives an account on this winter in his "Dagbog over mine Missionsreiser i Finmarken" (Diary of my missionary travels in Finnmark).

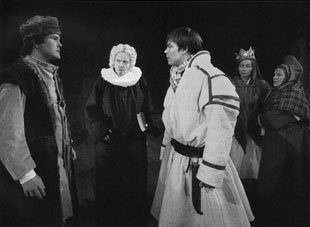

| J. A. Friis made a Sami grammar and dictionary and translated many religious publications to Sami. For a Norwegian audience he is probably most known for his novel "Laila". Here from Beaivváš Sámi Teahters performance in 2002.

(Photo: Ola Røe / Beaivváš) |

In 1851 Friis became the temporary reader and publisher of Sami translations. Nevertheless, some claimed that a Sami chair of teaching was an "inappropriate scientific luxury". Not until 1874 was Friis appointed ordinary professor in Sami and Kven, with obligation to do translations by virtue of his office. Friis put down an extensive effort in the lappology and published both grammar, dictionary and "Lappiske Sprogprøver" (Lapp (Sami) language samples). He also treated the old Sami religion, and translated Sami folk tales and myths. A great part of Friis' working time was spent translating religious scriptures to Sami. With the help of Lars J. Hætta, who also took part in the complete Bible translation of 1895, Friis prepared the first edition of the Sami hymn book with texts, service book and prayers in 1870. Through his production of articles, first and foremost in Morgenbladet, Friis raised a series of controversial issues on the Samis and their most important problems. By publicly drawing attention to the evident discrimination of the Sami minority, he started the debate on the Sami language and it's status, which has continued to a greater or lesser degree.

J. A. Friis was in the middle of this irreconcilable struggle. Among other things he claimed that a foreign language makes the word of God obscure, and makes the meaning of it easy to forget. It's like the sperm which fell on stony ground. In a journal from 1887 he writes: "Once and for all, no matter what happens, I need to enter a protest against the school-directive which are being followed now. I want to have a clear conscience, I don't want to carry the responsibility of not having protested."

The reason for the bishops view on laestadianism was the messages he got from the pastors of the difficulties they had with the obstinate laestadian parishoners. They were seen as enemies of the church, and had to be defeated. After meeting these parishoners himself, the bishop changed his view completely, and viewed them as the most important support of the church.

In clerical circles and within the missionary organisations the opposition to the Norwegianization had it's roots in the message itself: People were to get the word of God in their own language. This was along the lines of Martin Luthers intention.

In 1893 Peter Bøckman took on the bishop's chair in Tromsø after bishop Skaar. He agreed completely with his predecessor in the battle against the ruthless Norwegianization of the Samis in the school. He made several energetic appeals to the ministry to let the children have the Christian teaching in their mother tongue.

The Lapp-mission was also run along the same lines. The Bible were published in Sami in 1896, and with that a major task were solved. The other main task was to preach the word of God in Sami for the Sami. It was a tacit condition that the preachers should either be Samis or Norwegians who had grown up among the Samis. Gradually a greater part of the preachers in the Lapp-mission came from the south after all. The Norwegian Lapp-mission was lead by a self-proclaimed board of three men. Many reacted to the absolute board, and many local organisations transferred to the The Norwegian-lutherian Lapp-mission association, which were founded in 1910.

Emissary Paul Pedersen, who was connected to Trondheims home-mission circle, got words of the difficult schooling situation all the time. He raised the matter with his missionary company, and in 1910 Havika school home for Lapp children started in hired locals. When the work Trondheims home-mission circle had started among the Samis were transferred to The Norwegian Lapp-mission in 1911, Pedersen followed, and the Lapp-mission took on the school home in 1917. They bought the school building in 1924.

| The last class of pupils at the Sami school in Havika, before it was closed down in 1951

(Source: Samenes Venn / Rogstad: Streiftog i Samenes saga) |

What created the struggle concerning the Sami-school in Havika, was the completely non-Sami teacher- and servant-staff of the school. Especially the pupils from the inner and northern rural districts had difficulties in the beginning, because they didn't understand the teacher. In part the Lapp-mission met severe criticism for this, and several Sami critics viewed the school as a Norwegianization institution.

The war 1940-45 put a stop to the running of the school in Havika. The post-war period entailed a new opinion of the Samis. The injustice which the occupation force had demonstrated as the master race, threw a new light on the Norwegians as the master race above the minority-group. Despite of the protests raised at the school, at the time it was closed down in 1951 it was referred to as an important centre for both pupils and parents - a common concern which many southern-Sami gathered around.

In the years from 1899-1902 he and pastor Tandberg in Lebesby edited the paper "Sami Usteb". The paper was in Sami, and was published by the Norwegian Lapp-mission. When Otterbech left Finnmark in 1902, Tandberg was left alone with the editing until the end of 1903, when the paper was closed down, to the great sorrow of the Sami. Tandberg left Finnmark the following year. At this point the Lapp-mission didn't succeed in appointing a priest as preacher in Finnmark, and the layman Bertrand M. Nilsen was left as the only preacher in the Lapp-mission. The board had reached the conclusion that laestadian preachers was unfit to be sendt out missioning for the church.

From the 1880s the Norwegian authorities had done everything they could to take all the use of their own language away from the Sami in school. The teachers who used only Norwegian got a better salary than the ones who didn't have the conscience not to use some Sami. Otterbech used strong words against this, and once he wrote: - This forced system is carried out with a hard-hearted consequence. One can not think about it without feeling the deepest resentment. In the first decades of the 20th century the Norwegianization was carried through more consequently than ever in the schools. Vulgar-darwinistic ideas also gave the disdain for other races a seemingly scientific alibi.

To do something concrete about the language-situation, in 1911 Otterbech proposed for the Lapp-mission to start a youth school (folk high school) in Karasjok. For many years he was the editor of "Lappenes Venn" (The lapps' friend), and in the book "Kulturverdier hos Norges finner" [Cultural values among the Norwegian Lapps], he wrote important things about the church's role among the Sami. At a meeting in Bergen in 1910 four Lapp-mission organisations were united to Det norsk-lutherske Finnemisjonsforbund (The Norwegian-Lutheran Lapp-missionary association, commonly called "Finneforbundet". Jens Otterbech was elected the chairman of the main board. He met severe criticism for having established a new national organisation. His defence was that the "Finneforbundet" was to be something more than the domestic mission society, which had a Norwegian-coloured arrangement in Finnmark. Being questioned why the Lapp-organisation couldn't associate with the Norwegain Lapp-mission, Otterbech answered that the board of the Norwegian Lapp-mission wouldn't accept the demands which were made to a democratic organisation. Besides it put aside capital from collected means, instead of using the money straight away in the struggle for the Sami cause.

Shortly after the "Finneforbundet" was founded, the Norwegian Lapp-mission met all the demands which previously had been raised. After many and long negotiations the two organisations were united to the Norwegian Lapp-mission organisation in 1925. The two magazines "Lappenes venn" (the Lapps' friend) and "Norsk Finnemisjons Blad" (Norwegian Lapp-mission's magazine) were joined together to "Samenes Venn" (the Sami's friend). Beforehand the Lapp-organisation had made an enquiry to the Norwegian Lapp-mission asking if they would support the establishing of a Christian Sami folk high school if there was a union.

In 1917 Otterbech published the book "Fornorskningen i Finmarken" (the Norwegianization of Finnmark) together with the teacher Johannes Hidle. In 1918 Otterbech got the most votes at the bishop election for northern Norway, but due to his pacifist stand to the military, he wasn't appointed. In 1919 he handed in his resignation from his priest office and became the secretary-general of the "Finneforbundet". In this post he continued the battle against the Norwegianization pressure, and from his deathbed in 1921 he addressed a strong appeal to the "Finneforbundet" to found a Sami folk high school.

Both as priest and later missionary leader Otterbech wanted a brotherly collaboration with the laestadians. He always expressed the great significance the laestadianism had. After the unification the board made resolutions which directly hindered a collaboration with the laestadians. At the general assembly in 1945 Adolf Steen put an end to this, and afterwards the Sami-mission has gone for collaboration again.

| Sami-mission gathering at Šuoššjávri, between Karasjok and Kautokeino

(Photo: Hans Lindkjølen) |

It sounds nearly like a fairy-tale when the old people tell about their first years in school. The pupils came by foot, in river boat or by horse ride. The school premises were small and primitive, and were spread with up to a kilometres distance. Some at one side of the river and some on the other. Fetching water and sawing of logs were part of the daily programme. In the wintertime the arts and crafts teacher Olav Sunnseth walked several kilometres between the scattered houses every morning to light up the ovens.

The summer 1938 it was passed to build special premises for the school. The work was started, but in the spring 1940 the war put a stop to the work, and the school was closed. The construction work for the Sami folk high school in Karasjok wasn't resumed until in 1947. At this point the battle to get the school approved started. In 1948 Samordningsnemnda for skoleverket the coordination commitee for the educational system) stated: - It has to be a school raised and controlled by the state.

The superintendent of schools Lyder Aarseth was strongly behin that the Lapp-mission should be allowed to build and run the school. He wrote: - The school meet, as the first newly raised school building after the war in Finnmark, a flagrant need for teaching in the Sami-areas.

In 1949 the school was opened with 30 pupils, and Roald Svarstad as principal. The following year the ministry approved the plan for the school and its buildings, and gave it government subsidies due to the prevailing rules. From 1950 pastor Thor With took over as principal. The new school buildings were opened in 1951. The school plans for the first years clearly shows the double intentions of the school. It was to be a Christian folk high school with the subjects that were common at the time, meanwhile being a school where the Sami subjects had their place. All the time the Sami folk high school had Sami language, Sami cultural history, sewing of caps and national costumes, band weaving horn and bone crafts in its curriculums. The school worked actively to make the youths aware of all the things they owned in the Sami cultural heritage.

| The Sami folk high-school in Karasjok was of great importance for Sami youth. Here some pupil-works are exhibited.

(Addition in the internet-version: When we made the book we thought this picture was from the Sami folk high school. Later we've found out that the picture is from another Sami school where Hans Lindkjølen also has been principal; the Sami school in Troms, Målselv. We apologise the mistake, but can say that also in the Sami folk high school the pupils made similar things. Ed.)

|

The advocate of Sami language and culture, Odd Mathis Hætta, among other things, says about his school year at the Sami folk high school in Karasjok: - In Sami we lacked suitable textbooks and litterature. In our class none of us had been taught Sami before, but on the contrary through a mechanical form we had crammed Norwegian parts of speech, noun-forms, verb conjugations and a lot of other things. The primary school education we had received, had a small transfer value to learning Sami at the Sami folk high school. That we nonetheless got a good foundation for further schooling, in mathematics as well as Sami and the other subjects, is shown by the fact that several of us did further education after sitting under the teacher's desk of Kathrine Johnsen. Most of the pupils came from Finnmark. But all areas with Sami settlement in the country were represented.

Paul Ryan was principal at DSU at the time. In a memo he has given an explanation to this phenomenon. A father asked that his son should be spared from having Sami as a subject. When his wish wasn't met, this bitter remark was dropped: - You Norwegians have always controlled us Sami. And when we raise demands now, you refuse to take us seriously, on the grounds that we don't understand our own good.

In this period the school wished to be an eye-opener. In the psychological teaching they emphasised personal developent. To dare to be oneself, believe in ones own worth as a human being, develop freedom and independence was themes which were followed up in the cultural history teaching. The school's task became to make the youth conscious -to help them to a meeting with themselves. In stead of having a feeling of inferiority they should be proud of their fathers and mothers, who didn't succumb despite of a difficult existence. Very many have used the school as a stepping stone for further education. The school changed name from Den samiske ungdomsskole (The Sami youth school) to Den samiske ungdomsskole (The Sami folk high school) in 1964.

The reindeer-husbandry woman Ellen Marie Anti (Rávdul-Elle) had experienced poverty personally since childhood. She's a good example of the language-confusion in the inter-war period. When she came to the school dormitory at Smørstad in Lakselv in 1922, she didn't know it existed more than one language. She was born and raised in the mountains, and had never been in the village before. At Smørstad she was placed with children who only spoke Norwegian, some children who only spoke Finnish, and some who only spoke Sami, like she did herself. Her mother, who was illiterate, spoke both Sami and Finnish, so she grasped the Finnish relatively quick, but she didn't understand a word of Norwegian. The form master was a young southerner, who only spoke Norwegian. The school year was six weeks before Christmas, and six weeks after Christmas. During the third year of school Ellen Marie started to catch what the teacher said. When she quit school she spoke three languages fluently.

In 1930, when Ellen Marie was 16 years old and started confirmation school with pastor Alf Wiig in Karasjok, she had never seen a Sami book and could only read Norwegian. With Wiig all the teaching was in Sami. Because she couldn't read Sami, she got to borrow Norwegian books from Wiig. Later she learned to read Sami on her own. The wife of the pastor, Margarethe Wiig, who was in the middle of the language confusion, made a Sami ABC-book with her own illustrations, which came to be of great use in the Sami language teaching.

When she was asked to be part of different boards and assemblies, Ellen Marie always answered yes. She wished to be a part of the work to creat a more philanthropic society. In this way she stayed in the board of the Norwegian Sami mission and in the board of the Sami folk high school for many years. Her argument was: - I have always had the education and future of the youth on my heart. I want them to be a part of what I have missed out on myself. During my time as theory teacher at the Sami folk high school in the 1960s I once gave the following assignment for a paper: "Difficulties and problems I have met during my time in school".

One of my prosperous pupils among other things wrote the following: "-For us Sami the language difficulties are the worst, at least that's how it's been to me. From the first day you start school you have to start to learn a "foreign" language, namely Norwegian. It might sound a bit strange when I say Norwegian is a foreign language, but to us who started school 12 years ago it was. We had only spoken Sami at home, and otherwise when we were together with other children as well. We quite simply didn't speak a single word of Norwegian when we started school. After a couple of years of schooling I leaned some Norwegian, but far from enough to be able to speak properly. Sami was banned in the third grade. After that you weren't allowed to speak Sami in the lessons according to the regulations. If you weren't able to answer the things which were asked in Norwegian, you got a lot of scolding for not doing your homework properly. If you tried to answer in Sami, you got this answer: It should be clear by now that we speak Norwegian at school.

When I had crammed Norwegian for a whole lesson, I got out in the break and spoke Sami. In the dormitory we also spoke Sami, and of course when i got home. What else did this lead to, apart from me starting to mix two entirely different languages. In the end I didn't dare to say anything because I didn't want to make a fool out of myself. I can still feel this fear, but more seldom now... All the things that has to do with Norwegian I have dreaded and hated all my life -and maybe I'll continue doing that...."

Another time I gave the following assignment for a paper: "The heritage of our fathers -a burden or a ballast for life". The same student then wrote, among very many other things: "... the language is probably the most important thing a people can inherit from their ancestors. The Sami language is important to us who wants to be Sami. The ones who tries to deny their Sami origins tear down, step on and destroy what the ancestors have given them. This is directly a sin to the fourth command... the heritage of our fathers will most probably be a ballast for life than a burden, as long as we want to be ourselves, as long as we're willing to carry the heritage of our fathers on."

After running in fifty years the Sami folk high school was shut down in 1985. The last ten years were marked by insecurity in many ways. There weren't enough Sami youth applying for the school anymore. The educational need was covered by the public school, although subjects such as duodji (Sami handicrafts) still was behind. The discussion on Sami language and culture continued to grow more intense throughout the 1960s. The struggle was characterised as a linguistic civil war in Karasjok by some, and to a great extent followed the borders between the political parties. In short it concerned the "right of life" of the Sami language in school and in everyday life. In this struggle the Sami folk high school with its majority of Norwegian teachers ended up in the middle of the line of fire from younger Sami, who could express themselves like this: - For hundred years the Lapp mission has followed us Samis from the cradle to the grave. This form of public guardian has to come to an end now.

Many of the elderly were nonetheless positive to the school, which had given them a good start in life, and among other things after encouragement from them the school was started again. But the supply of pupils was so small that the running of the school had to be stopped again after a few years.

At the closing of the school, the former principal of the school, Thor With, among other things said.: - After 50 years of service for Sami youth the Sami folk high school is no longer an offer. It has done its service - a very important service. Ever since the first year it started this school has had to fight for its existence. First of all it had to gain trust among Sami youths, and it did. It also had to fight for its place with the authorities and with the sceptics of mission.

In an interview a former pupil at the Sami folk high school once said: - It was a good place to be. This is where I realised who I were myself. This is where I got the courage to look ahead, and the belief to look up.

| A Sami service in Akershus "castle-chapel". At the pulpit: Jacob Børretzen from the Sami Mission (right) and interpreter Hans Eriksen. (Photo: Hans Lindkjølen) |

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5]

More articles from Sami school history 1